Internet resilience is usually considered from a technical point of view, with little consideration given to social implications that impact connectivity decisions.

Pakistan offers a vivid example of this: connectivity is shaped by local power relations, states’ security-oriented considerations, and the increasing dominance of content-delivery platforms over the Internet.

To better understand the effect these processes have on Internet resilience, using Pakistan as a case study, my colleagues and I at the French Institute of Geopolitics (IFG), University Paris 8, and LUMS University developed an innovative methodology that combines qualitative social science methods and standard network measurements.

An Over-Concentrated Network

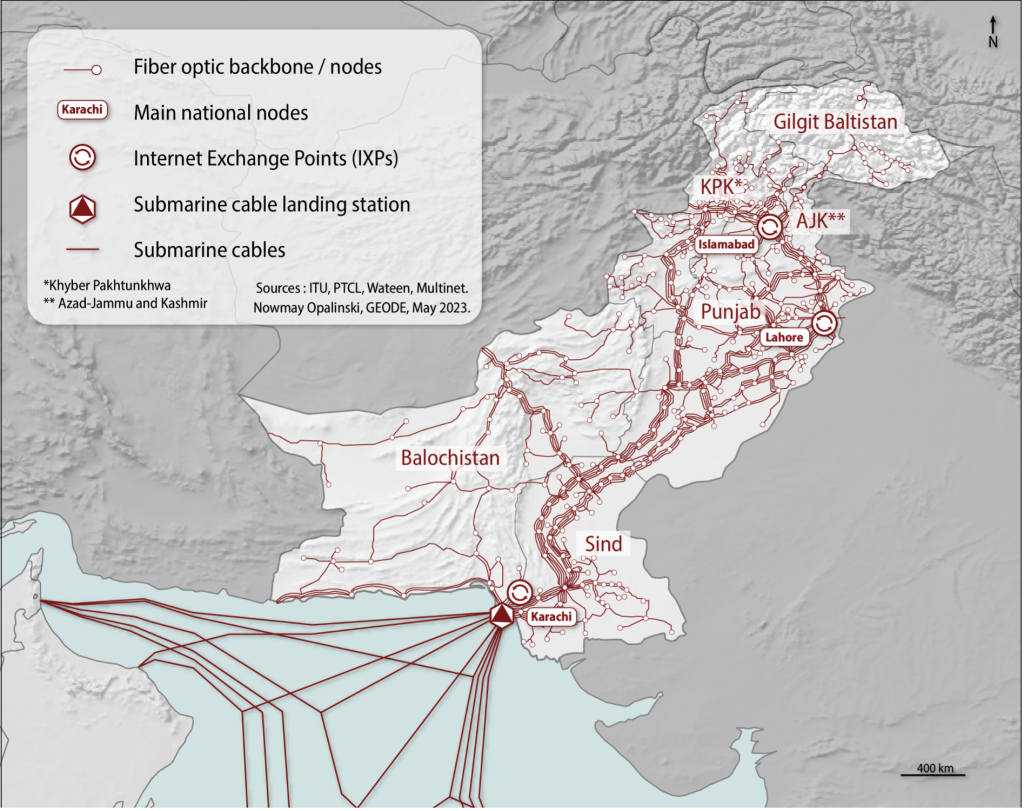

At the physical level, Pakistan’s connectivity is characterized by a high degree of concentration and a lack of diversity due to local conditions impeding further infrastructure development.

Internally, connectivity is concentrated along the main transport corridors linking the country’s north and south along the Indus River. Few Internet Service Providers (ISPs) have a countrywide fiber network implantation because of the difficulties of gaining right-of-way access from various rent-seeking stakeholders. Enduring instability in the western provinces has also limited the construction of additional redundancy rings. As such, the incumbent operator, PTCL, is the only ISP able to connect the whole country, resulting in smaller ISPs’ dependency on its infrastructure.

A High Dependency on Subsea Links

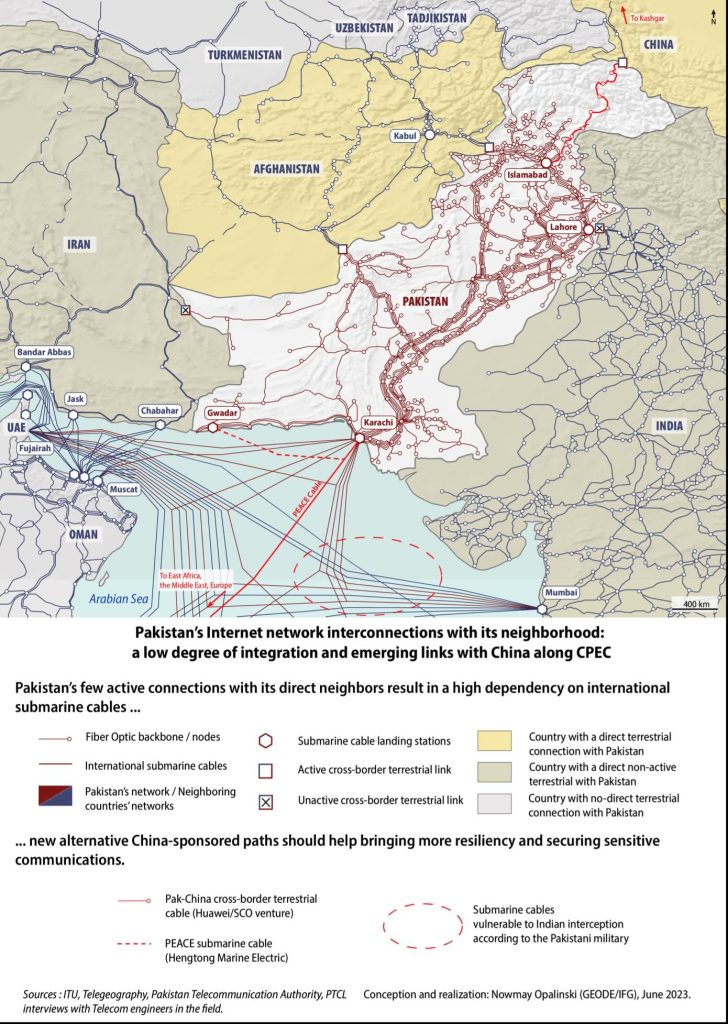

Pakistan’s international connectivity is also overtly concentrated, with all the subsea cables landing at a single location in Karachi. Moreover, only two ISPs operate landing stations: PTCL and TWA.

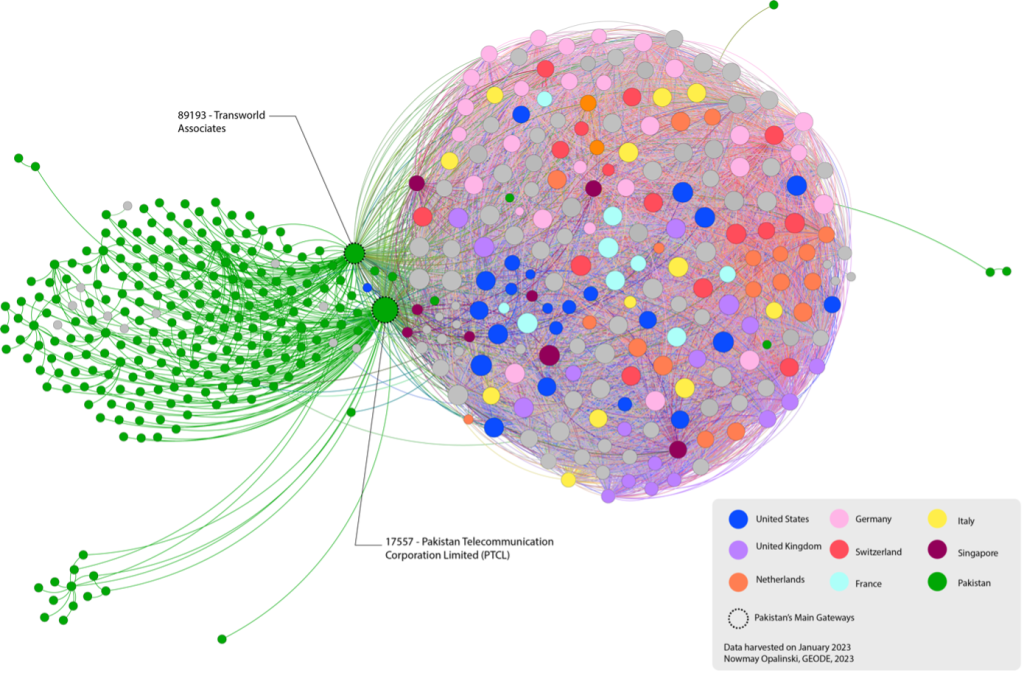

When looking at BGP agreements through spatialized graphs, it’s evident that both PTCL and TWA play a central role within Pakistan’s domestic connectivity because of their unique roles of gateways towards the global Internet.

Pakistan also lacks terrestrial links—which could provide backup options in case of subsea cable disruption—because of the state’s security outlook. Interconnecting with networks located in India is strictly prohibited, whereas Afghanistan is primarily a client of Pakistani ISPs. Connectivity with Iran is also non-existent because local actors fear being targeted by US extra-territorial sanctions.

Islamabad instead favors backup options with China. Yet, local ISPs still question the interest of such a connection since China does not host any content of interest for Pakistani users. Thus, subsea cables remain the only feasible option for accessing international connectivity.

Such a dependency on submarine links is even more problematic as most of Pakistan’s national traffic is constantly driven overseas. Therefore, any disruption of subsea cables, or within the country along the axis connecting Karachi to the rest of the inland regions, results in a significant downgrade of Internet access. This is what happened in August 2022 when a historical monsoon caused large-scale floods, causing multiple cuts along the country’s backbone.

Platforms’ Dominance Over Data Traffic

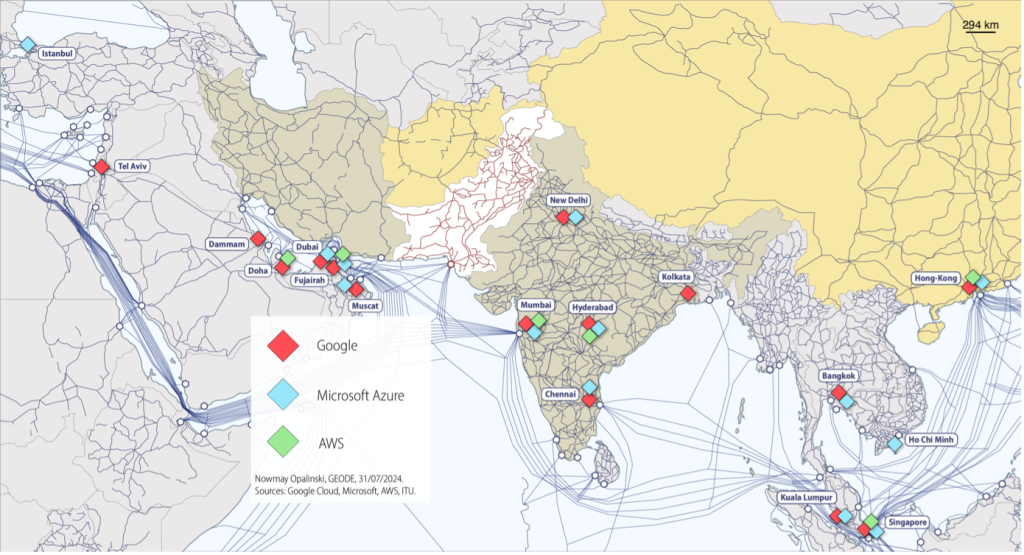

To tackle the issue of over-dependency on international traffic, the Pakistani government has tried to enforce local hosting, yet content-delivery networks are still reluctant to set foot in the country as they have deployed their infrastructure elsewhere in the region.

India has become the rear base of US-based platforms for their services within South Asia, yet Pakistani ISPs cannot interconnect with them. Pakistani ISPs instead plan to increase their subsea capacities towards the Arabian Gulf, as platforms are installing their points of presence in the UAE, Oman, and Saudi Arabia.

Therefore, Internet resilience results from constant negotiations between ISPs, content-delivery networks, and states. Currently, content-delivery networks are driving the demand for data traffic and subsequently shaping ISPs’ connectivity choices, which are also restricted by states’ own security red lines.

Read our paper presented at AINTEC’24 to learn more about Pakistan’s connectivity and our methodology.

Nowmay Opalinski is a Ph.D. Candidate at the French Institute of Geopolitics at Paris 8 University and a member of the research project GEODE (Geopolitics of the Datasphere). His research focuses on the geopolitical underpinnings of Internet connectivity in Asia.

Contributors : Zartash Afzal Uzmi (LUMS University), Frédérick Douzet (Paris 8 University).

Photo by Jack Sloop on Unsplash